|

|

|

THE WORD

Vladimir Nabokov

![]()

![]()

Carried away from a terrestrial night by the inspired breeze of a dream, I found myself standing by the edge of a road, under the clear, unintermittingly golden sky of an extraordinary mountainous country. Without even looking I could sense the gleam, the angles and facades of the colossal tessellated cliffs, the dazzling chasms and the reflecting glare of many lakes lying somewhere below and behind me. My soul was seized by a sensation of divine iridescence, freedom and elevation, and I knew that I was in Paradise. Yet in my earthly soul a single earthly thought stood out like a piercing flame - and how jealously, how harshly did I guard it against the breath of gigantic beauty that surrounded me… That thought, that naked flame of suffering, was the thought of the earthly country of my birth. Barefoot and destitute I stood by the edge of that mountain road and awaited the merciful, the radiant celestial beings. And the wind, like a premonition of wonder, played in my hair, filled the ravines with a crystal-clear rumble, stirred the fairytale silks of the trees blooming between the crags along the road. Long tufts of grass licked up at the trunks like tongues of fire. Large flowers unfurled their transparent, bulging petals, broke smoothly loose from the shining branches and drifted through the air like flying chalices filled to the brim with the sun. Their scent, damp and sweet, reminded me of all the best things I had come to know in life.

And suddenly the road on which I stood, suffocated by this splendour, was teeming with a tempest of wings… Out of some blinding depths there arose the multitude of angels I had been waiting for. They seemed to tread on air with the motion of coloured clouds, faces impassive, only their radiant eyelashes quivering exaltedly. Turquoise birds soared between them, bursting into exultant girlish laughter, and lithe, orange creatures with quaint black speckles bounded in their midst. The animals twisted in the air as they soundlessly cast out their satin paws to chase the floating blossoms, and circling, soaring they swept past me, shiny-eyed.

Wings, wings, wings! How can I relate their sinuosities and shades? They were powerful and soft - red-brown, crimson, rich blue, velvety black with fiery powder on the round tips of the arched feathers. These steep clouds rose impetuously over the glowing shoulders of the angels. Suddenly one of them, in some fit of wonder, as if unable to contain his blissfulness, threw open his winged splendour for just one instant, and it was like a flash of sun, like the glare of a million eyes.

They thronged past, gazing upwards. And I saw: their eyes were exulted chasms and the last glimmering of flight was in their eyes. They glided through the rain of flowers, spilling their moist splendour about in the air. The smooth, bright animals whirled and soared playfully. The birds rang out, blissfully darting up and swooping down, and I, a dazzled, trembling pauper, stood by the edge of the road, with the same thought still gibbering on in my impoverished soul - to beg them, to beseech them to listen to my words; that on the fairest of God's stars there is a country - my country - dying in excruciating gloom. I thought that if I could seize just one handful of this quivering reflection I would bring such joy to my country that the souls of men would instantly light up and begin whirling to the splashing, rustling sounds of resurrected spring and the golden boom of woken cathedrals…

And I stretched out my trembling hands, trying to bar the angels' way. I clutched at the edges of their raiment and the ardent, undulating fringes of their arched feathers, but they slipped through my fingers like blossoms of down, and I moaned and floundered and frenziedly implored them to take pity on me. On and on the angels went, not noticing me, their finely carved faces turned aloft. Their throng was speeding to a heavenly feast at an unbearably bright patch of light where the Divine Being breathed and swirled. Him I did not dare even contemplate. I saw fiery cobwebs, sprays, patterns on the gigantic, flaming red, russet, purple wings. Above me waves of down went rustling past. The turquoise birds darted about in iridescent haloes, and everything swam in the flowers that broke loose from the glistening branches…

"Wait, hear me out," I cried, trying to embrace the light angelic feet, but their soles, intangible, ungraspable, slipped through my outstretched hands, and the edges of their broad wings only singed my lips as they fluttered past. And in the distance the golden patch of light between the lushly and distinctly coloured cliffs was filled by their splashing tempest. They were leaving, leaving. The high, agitated laughter of the birds of paradise was dying away, the flowers no longer took off from the trees. I grew weak and quiet…

And then a wonder occurred: one of the last angels had fallen behind, and now turned around and quietly approached me. I could see the deep, fixed, diamond-like eyes under his impetuously arched brows. Something like hoarfrost glimmered on the ribbing of his dilated wings, and the wings themselves were of an indescribable grey hue, every feather ending in a silver crescent. His countenance, the outline of his faintly smiling lips and straight, clear forehead reminded me of features I had once seen on earth. It seemed as if the contours, rays and charm of all the faces I had loved, the faces of those long departed from me, had flowed together in one miraculous countenance. It seemed as if all the familiar sounds that had once caressed my ears were now collected in a single, perfect melody.

He was smiling when he walked up to me, and yet I could not look at him. Only when I caught a glimpse of his feet did I notice a fine netting of pale-blue veins on his soles and one pale birthmark, and from these veins and this little blemish I understood that he had not yet completely turned away from earth, that he would be able to understand my prayer.

And then, lowering my head and pressing my scorched hands, soiled by the bright clay, to my dazzled eyes, I began to tell him of my sorrow. I wanted to explain to him how beautiful my country was and how terrifying its deadly slumber, but I could not find the right words. Hurrying and repeating myself I gushed on about some trifles, about a burnt down house where once the sunny lustre of floorboards had been reflected in an inclined mirror, of old books and old lime trees I gushed, about bric-a-bracs, about my first poems in a cobalt blue schoolbook, about some grey boulder overgrown by wild raspberries in the middle of a field full of scabious and camomile, but the most important thing I could not express - I fumbled, stuttered, began afresh, and once again helplessly pattered on about the rooms in a cold and resonant country estate, about lindens, first love, bumblebees sleeping on scabious… It seemed to me as if any moment now I would get to what mattered, would explain the whole sorrow of my country; but for some reason I could only remember the tiny, wholly terrestrial things that can neither speak for themselves nor shed those large, scorching, terrifying tears about which I wanted to, but could not talk…

I became quiet and raised my head. Motionless, with a quiet, attentive smile, the angel fixed his oblong diamond eyes on me - and I sensed that he had understood everything…

"Excuse me," I cried out, and timidly kissed the little birthmark on the bright heel. "Excuse me for only being able to speak about the small, the transient. But you understand, don't you? Then answer me, merciful grey angel. Help me. Tell me what will save my country."

And fleetingly embracing my shoulders with his wings, the angel uttered a single word, and in his voice I recognised all the beloved voices that had fallen silent. The word he spoke was so beautiful that I closed my eyes with a sigh and lowered my head even further. It was a word that overflowed in fragrance and resonance through my tendons, the sun rose in my cerebrum, and the innumerable ravines of my consciousness picked up and repeated the heavenly, radiant word. It filled me; it was the thin knot that drummed at my temples, the moisture that trembled in my eyelashes, the sweet coldness that wafted through my hair, the divine heat that flooded my heart.

I cried out the word, taking delight in each syllable. I fitfully threw up my eyes in radiant rainbows of blissful tears…

Lord! Winter's first green light is shimmering in my window, and I do not remember what it is I cried out…

Published in the "Rul'" of 7 January 1923

TRANSLATOR'S AFTERWORD

This is one of the very first published short stories by Nabokov that we know of. It appeared in the "Rul'" of 7 January 1923, and it is probably not coincidental that the date of publication coincides with the Orthodox Christmas. For someone not acquainted with Nabokov's earliest Russian works the strongly religious undertones and imagery (as close to "conventional" as Nabokov would probably ever get) will be, to say the least, surprising. The year of 1922, when Nabokov wrote this story, was dominated by the severely traumatic event of his father's murder in the Berlin Philharmonic Hall. We can expect the time frame of composition to be very close to similar works of this period such as Nabokov's very religious (untranslated) poem "Easter", so gloated over by Field and glossed over by Boyd.

This is a time in the young Nabokov's life when his literary output shows a single-minded occupation with the idea of death. The theme of angels, too, is an important one in the early poetry of Nabokov, including the very early cycle "Angels" (written between 1918 and 1920) and the poem "On Angels" in 1924. These are messengers capable of moving between our own world and another - but they are also endowed with another feature that comes strongly to the fore in this story - a physical resemblance to butterflies. I leave it to future researchers to look closer at that one.

If we concede to Véra Nabokov's statements regarding the importance of "potustoronnost'" ("otherworldliness") as one of the central "themes" of her husband's work, what we have in this story is an early attempt by the young Nabokov to describe that "other world" in words , or rather to describe someone else's attempt to describe that world. This stands in stark contrast to Nabokov's later work where we can at most but catch a slight glimpse of that other dimension through its obscure reflections in this world.

As such the rather purple prose of "The Word" could seem a failed experiment; and yet what makes this story interesting against the background of Nabokov's larger oeuvre is the irony that it is itself a record of that very same failure -- the failure of the narrator to convey in words his dreamed experience is also a lesson to the young author. The overwrought ornateness of the language belongs to the narrator, in much the same way as "Lolita"'s fancy prose style belongs to a murderer, not the author. Narrator and author alike have begun to realise the limits of language in breaking through to that world. The other world is unknowable in this one, and one can only vaguely hope to recreate something similar to its perception through the careful mimicking of its subtle encroachments into our own world. As for the rest...

"And that secret, ta-ta, ta-ta-ta, ta-ta,

But more than that I may not tell you…"

--- Translation and Notes by L.V.

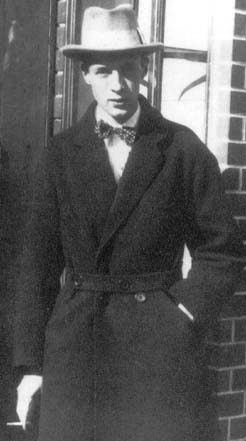

Vladimir Nabokov in 1923

(Photograph: Ardis)